“Knowledge can influence the pruner’s behavior. Instead of giving ‘shape’ to the tree, [they] should be encouraged to follow the free tendencies of the variety by enhancing the natural qualities of the tree and controlling its weak points; this is called ‘training.'”

— Lespinasse & Lauri

Traditionally, training referred to pruning fruit trees into a specific shape (central leader, modified central leader, espalier, tall spindle), regardless of their natural growing habits. To maintain an artificial shape, you must prune annually for the tree’s lifespan.

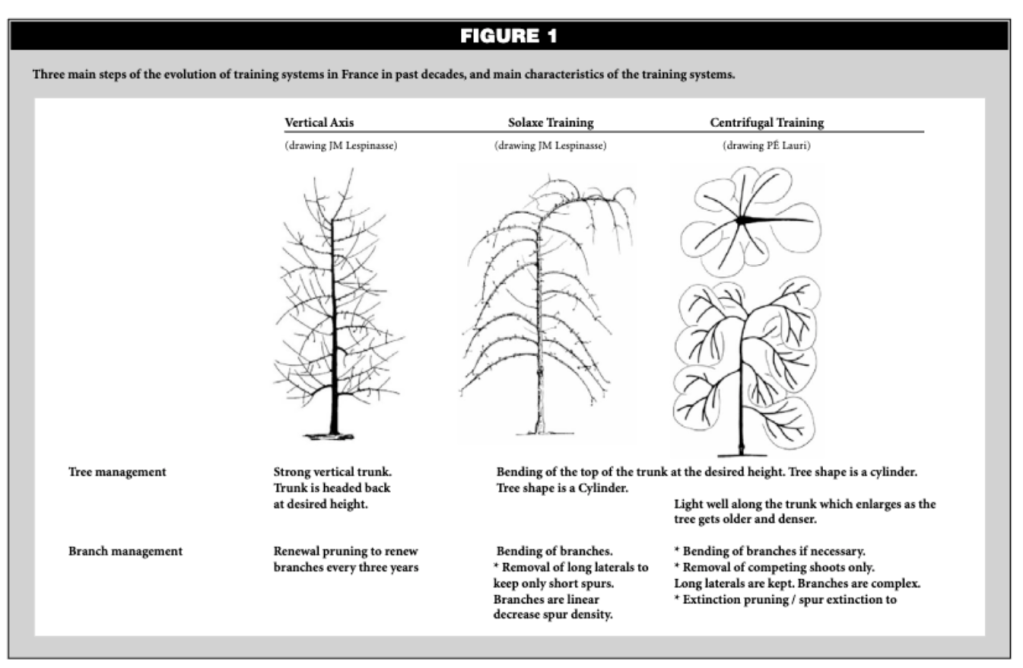

Researchers at INRA in France have been leaders in exploring methods of training which respect the way in which fruit trees prefer to grow and fruit, reducing or eliminating the need to prune.

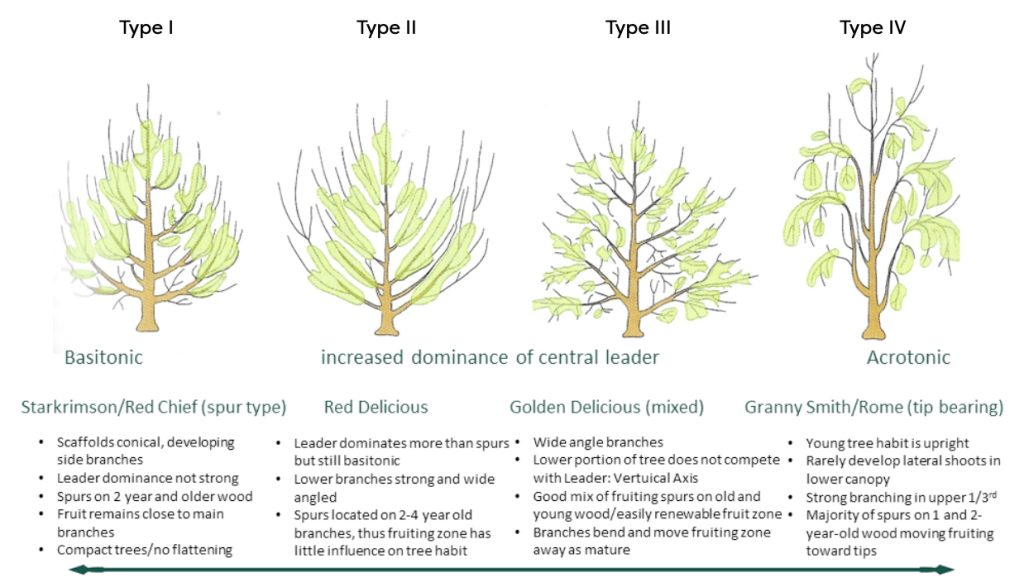

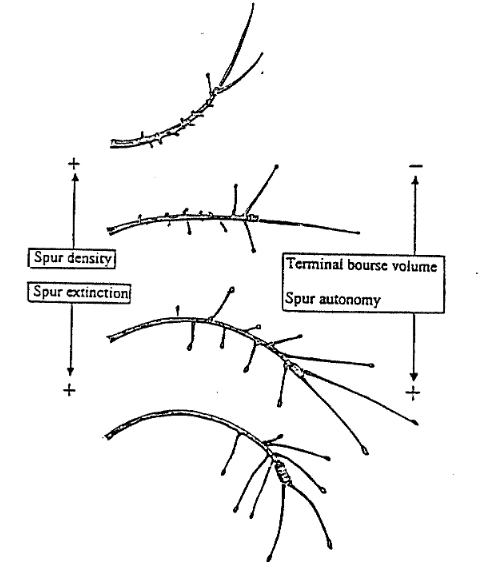

Every cultivar has their own architectural strategy, including: acrotonic tendency (favouring top growth vs lower growth), branch habit, crotch angle, shoot length, position of fruit on branches, flowering behaviour and rate of spur extinction.

Why train instead of prune

Instead of pruning, IRNA recommends getting to know your particular cultivar, “enhancing the natural qualities of the tree and controlling its weak points; this is called ‘training.'”

Trees usually train themselves — the weight of fruit naturally bends branches below horizontal. Below horizontal is the optimal branch position for most fruit trees (except pears, which should be trained to horizontal). Training can can help a tree fruit earlier by altering the flow of auxin, favouring fruitful buds rather than vegetative buds. For cultivars with strong crotch angles that bear biannually, training branches below horizontal (to a 100-120 degree angle) can help them bear more regularly. Focusing on training rather than pruning helps reduces suckers, especially in plums.

For ease of harvest, you can also control a tree’s final height by bending the lead branch, breaking apical dominance so it begins bearing fruit rather than continuing to grow taller.

Stefan Sobkowiak, in his permaculture orchard, uses INRA’s research to inform his approach to fruit tree training and pruning.

Supporting fruitfulness

The more horizontal the branches and shoots, the more they droop, the more fruit their buds produce. As a result, Lespinasse recommends:

- Promoting vegetative growth in the first year, applying compost and watering as needed.

- Allowing the tree to branch as much as possible — the more shoots, the shorter they’ll be and the more rapidly they’ll bear fruit. Weight of the fruit then help the branches bend naturally. Removing branches or branch tips unbalances the tree and delays fruiting.

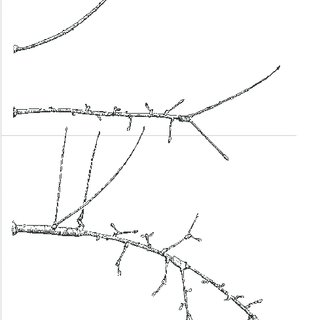

- If branches are too vertical, bend them to reduce the dominance of the terminal bud (the upper most bud) and promote a more even distribution of nutrients and carbohydrates along the length of the limb. This induces fruiting spurs and increases lateral branching along the entire limb.

When to train

Training in summer — July or August — is ideal. The weather is warm, branches are flexible, terminal growth has ceased and branches are no longer actively growing fatter. Summer training also helps prevent suckers from developing from the upper portion (arcs) of branches trained horizontally.

Summer training also allows time (2-3 months) for lignin to accumulate and branches to settle into their new angle, allowing you to remove wires or ropes in late fall or winter. If you’re eager to increase fruiting for the following year, you could train in May but this will probably stimulate suckers.

Train branches using strings, tree training bands, treeform v-spreaders, clothespins or Sobkowiak’s favourite method, 12-gauge wires. He cuts the wires to 30, 60 and 75-90cm lengths, twisting and flattening the ends so they’re not dangerous.

Train branches, not the tree

For small branches, you can simply bend them until they crack, laying them downward. If the soil biology is good, the tree quickly repairs the crack. This eliminates the need to shape the branch using wires or other tools in the future. To reduce the risk of infection, don’t prune or crack branches if it’s raining or if rain is in the forecast.

For larger branches, use one hand to hold onto the branch where it meets the trunk. With the other hand twist towards you and gently but firmly push the branch down until it’s in the desired position. Hook a wire or use a rope to anchor this branch to another one to keep the branch in its new, downward position. When bending, you can also angle branches left or right to ensure branches are evenly distributed around the trunk.

If a branch is greater than 50% of the size of the main trunk, mark it for winter pruning.

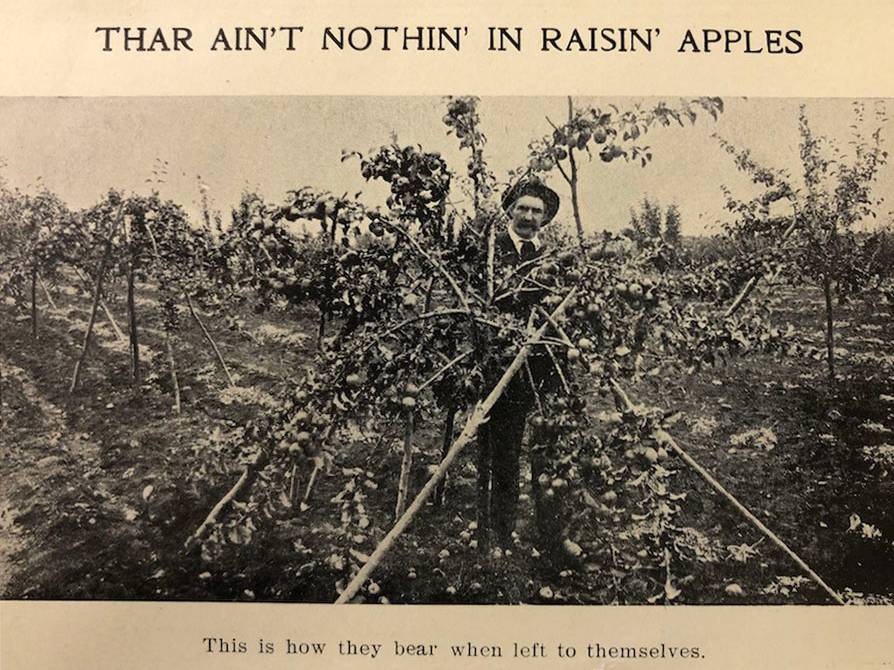

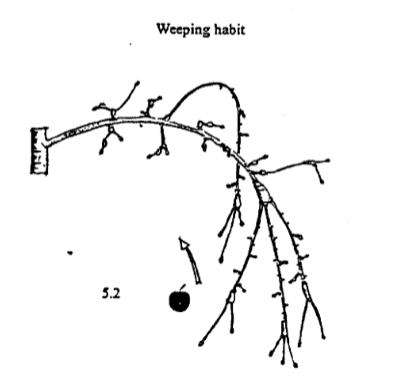

If you compare the natural shape and the branch angle of the apple cultivar in this picture with the diagram of tree cultivar shapes, you’ll see it most closely matches Type II, 30 degree branch angle. This means that this tree is likely alternate bearing. Training the branches to below horizontal should help the tree bear more regularly.

Training branches below horizontal also helps reduce fruit load thanks to a phenomena called spur extinction. Trees with strong branch angles have a tendency to bear bi-annually, producing all of their spurs in one year resulting in heavy fruit loads that require thinning.

Branches which are below horizontal naturally self-regulate their spurs, ceasing growth of some which results in their death (extinction) while stimulating others to become bourse shoots. In spring (or during winter pruning) you can further reduce the number of spurs with a technique Sobkowiak calls the final polish, removing spurs in the chimney and under branches with your gloves. This increases light penetration, further encourages annual bearing and eliminates the need for thinning.

Managing suckers

Sobkowiak urges us not to “get suckered into suckers” as they’re not the problem, they’re the symptom of a wrong branch angle. If you allowed your tree to develop naturally without pruning, you’ll have fewer suckers (also known as epicormic branches, reiterations or water sprouts). If suckers do form, the most likely locations are along the arc of strong fruiting branches or the top of the tree if the main leader is bent. If the branch angle is good, suckers should bend naturally as they fruit, becoming replacement branches.

If a branch didn’t fruit early enough, it may set into a strong 45 degree angle and will sucker. If you prune these suckers, you’ll get more suckers. Instead of pruning, Sobkiwiak suggests:

- If the sucker is in a gap, convert it into a fruiting branch by bending it, cracking it if needed (ensuring enough bark remains for the wound to heal)

- Crack remaining unwanted suckers, ensuring less than 50% of the bark remains attached which allows the wound to heal and prevents suckers from bouncing back

- If the branch is still young enough, train it to a 100-120 degree angle

- If the branch is older and set in its angle, prune it off and train a replacement branch

References

- Developing a new paradigm for apple training, Pierre-Eric Lauri

- Influence of fruiting habit on the pruning and training of apple trees, (Lespinasse & Lauri, 1996)

- Apple tree architecture and cultivation – a tree in a system, P.E. Lauri, 2019

- Training and pruning apple trees, Amaya Atucha, T.R. Roper, Wisconsin Horticulture

- Apple fruiting: spur, semi-spur, tip and partial-tip varieties, Home Orchard Society

- F-114R: Limb positioning, UMass Extension Fruit Program

- Spreading shoots of young apple trees, Bas van den Ende