“The persimmon is remarkable in the length of its fruiting season. With the persimmon, nature unaided has rivaled the careful results of man with the peach and apple, for the wild persimmon ripens often in the same locality continuously from August or September until February, dropping their fruits where animals can go and pick it up through this long season of automatic feeding.”

J. Russell Smith, Tree Crops: A permanent agriculture

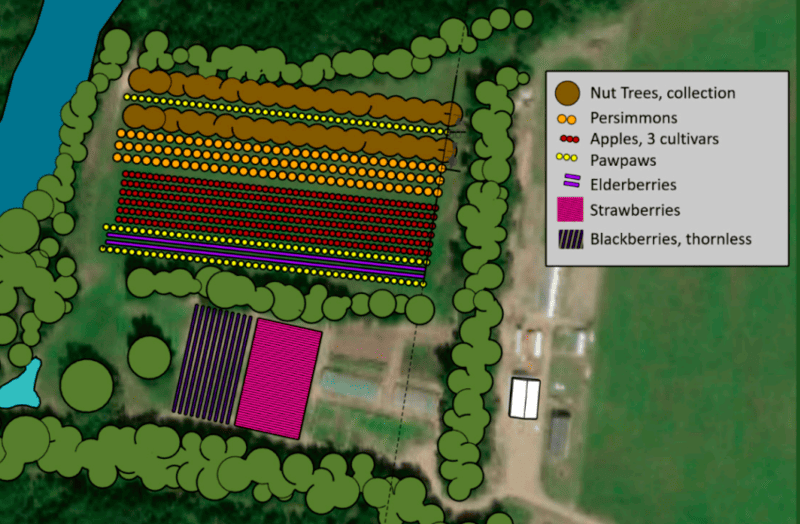

Spring 2025 we planted six American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) cultivars — Szukis, Peiper, Gordon, Prok, Yates and Campbell NC10. They join the American Persimmon seedlings we planted in the Edible Little Nut Forest in 2021. We’re eager to get to know the various expressions of American Persimmon, whose energy-dense fruit, high in fiber, rich in vitamin A and full of antioxidants — including anthocyanin, beta carotene, flavonoids, tannic acid and vitamin C — fruit ranges in size from small crabapples to large tomato-sized fruits.

Persimmons are North America’s largest berry

Persimmons are the most nutrient dense native fruit in North America and the only member of the ebony family. A 1915 article by W.F. Fletcher in the Farmer’s Bulletin describes Persimmon as having:

“the longest season of any fruit, with the earliest and latest varieties growing side by side… In the District of Columbia there are some trees which ripe their fruit in August and others on which it hangs until February.”

They’re considered native from southern New England across to Kansas and southward to Texas, though fossils have been found in Miocene deposits in areas of Greenland and Alaska so their range was once much further north:

“There are those who suspect the fruits of the American persimmon to be a throwback to a time when animals like woolly mammoths and ground sloths roamed this continent, dispersing persimmon seeds as they roamed across the terrain. Indeed, fossils of American persimmon have been found in Miocene deposits in areas of Greenland and Alaska which suggests that this species has undergone range contraction, potentially due to the loss of these large seed dispersers. However, modern day evidence would seem to suggest otherwise. Today, much smaller animals like raccoons and opossum seem to do just as good of a job as a larger animal would. It is likely that the constricted range of the American persimmon has more to do with climate than seed dispersal.”

How did they come to be native to southern New England, Kansas and Texas? Why do they have the longest season of any fruit? Who are the people we should give thanks (and potentially royalties) to for their work before us? These are questions Eliza Greenman, who researches the genetics, history and breeding of American Persimmons, is asking. She works for the Savanna Institute, which is stewarding high-density nurseries with tens of thousands seedlings harvested from existing, wild-found cold-hardy varieties.

“Why do we care about tracking northern persimmons through southern persimmon belt?… when you’re working with a fruit that is essentially novel and hardly domesticated, it’s really important to start carrying with you the idea of paying some sort of attribution and respect and giving a lot of credit to those that came before us that worked with these fruits and nuts and their selection processes in order to… carry that forward and you want that to be part of the story.”

Pasimenan or Pessamin or Putchamin are Algonquin words for Persimmon. The Mississippian Mound site excavations — constructed by the Mississippian culture who built urban settlements and satellite villages in the southeast from approximately 800 to 1600 CE — reveal a high percentage of Persimmon seeds. Mound 51 is known as Persimmon Mound. In 1791 William Bartram, travelling through Choctaw country:

“observed in the ancient fields….Persimmon….diospyros….[Choctaw] inform us, that these trees were grown by the ancients on account of their fruit, as being wholesome and nourishing food. Though these are natives of the forests, yet they thrive better, and are more fruitful in cultivated plantations and the fruit is in great estimation with the present generations of [the Choctaw nation].”

Persimmons, both wild foraged and cultivated in community orchards, remain a culturally important crop for the Osage Nation.

Persimmons are gender fluid

Persimmons can be either dioecious (staminate and pistillate flowers on separate trees), partially self-pollinating or fully self pollinating. Pollen from a female cultivar can be used to pollinate another female cultivar, and the progeny of that pollination will be female.

“To complicate matters further, a tree’s sexual expression can vary from one year to the other and many cultivars of persimmon are parthenocarpic (setting seedless fruit without pollination).”

To ensure fruit, we’ve planted named cultivars. We’ve also planted a number of seedling Persimmons in the hedgerows and little forest. Here’s how we’ll check gender once they do flower. If they’re staminate they won’t produce fruit, but we could potentially graft branches with pistillate flowers onto these trees.

Interested in digging deeper into the history and genetics of American Persimmons? Read Andy Ciccone’s excellent article and Solomon Doe’s article on the various expressions of a native Persimmon.

How to eat a Persimmon

We planted our first Persimmon trees in 2020. What a joy to discover that in 2025 — despite the long drought — one tree gifted us with a bountiful harvest of gorgeous orange fruit. Although the label fell off this tree, based on the receipt and the fact that the non-fruiting Persimmon still has their Nikita’s Gift tag, I’m pretty sure this is Prairie Star, one of the earliest ripening American Persimmon varieties “prized for its unusually large, very sweet, firm and flavourful fruit.”

Due to their high tannin content, Persimmons are astringent unless fully ripe (mushy)! Even ripe, their skin remains astringent. Constance, when tasting her first Persimmon, made the mistake of biting into the skin. Astringency makes the mouth feel dry, causes puckering, numbs the tongue and constricts the throat.

Constance tries again, avoiding the skin this time.

There’s three ways to eat a ripe Persimmon: politely, sorta politely and in-the-garden style. Constance soon mastered how to eat them garden style.

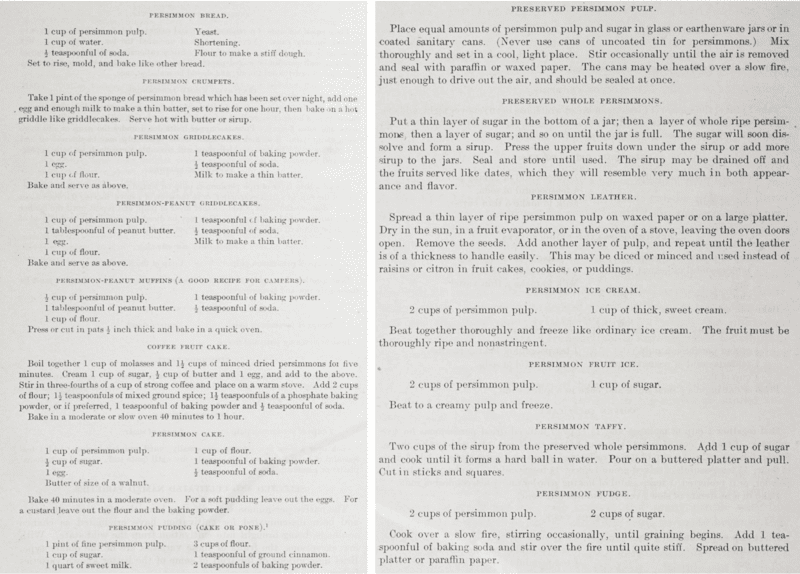

You can also pick firm Persimmons and ripen them on the counter. The Native Persimmon, an article by W.F. Fletcher in the 1923 Farmer’s Bulletin, has some wonderful suggestions for preserving and cooking with Persimmons.

Ignore the myth about native Persimmons need frost to ripen. In our area Persimmons, if they have northern genetics, will drop to the ground throughout the fall season as they ripen. If Persimmons with southern genetics are planted too far north, the growing season is too short for the fruit to ripen so they hang on the tree.

Many of our wild kin love Persimmons

Persimmons are also an important food for many of our wild kin. More than 45 butterfly and moth species, including the incredible Luna Moth, feed on their leaves. Insects who feed on the nectar or pollen include Bumble Bees, little Carpenter Bees, Digger Bees, Cuckoo Bees, Leaf-Cutter Bees, Mason Bees, Halictid Bees (including Green Metallic Sweat Bees), Syrphid Flies and Skippers and Honeybees.

Birds also love the fruit. Lou Orr, the person who took this picture of a Hummingbird feeding on Persimmon, also photographed a Downy Woodpecker, Northern Mockingbird, California Scrub Jay, Cedar Waxwing, American Robin and several Fox Squirrels feeding on the fruit. Who might feast on Persimmons in the Kingston area? In addition to those from our area listed above, birds likely to enjoy the fruit include Eastern Bluebirds, Yellow-Bellied Sapsuckers, Pileated Woodpeckers, Yellow-Rumped Warblers, Northern Mockingbirds, Gray Catbirds, Cedar Waxwings and Mallards.

There are a lot of pictures like this one of Raccoons doing acrobatics to harvest ripe Persimmons. Other mammals who enjoy the fruit include Foxes, Coyotes, Squirrels and Deers. Waiting for fruit to drop at Lakeside to harvest is problematic as within a day someone has munched on the fallen fruit.

Even Butterflies love incredibly sweet fallen fruit.

Persimmons thicket as a survival strategy when the mother tree dies or is damaged by fire, rabbits, deer or humans. We’ll encourage the Persimmons planted in hedgerows to thicket as thickets are fabulous bird habitat.

Let’s plant more Persimmons in Kingston

Persimmons — who thrive in poor soil, are drought tolerant and incredibly disease resistant — are fabulous trees that we should be planting in food forests, hedgerows, thickets and birdscapes throughout Kingston. Sarah Lovell, a researcher focused on sustainable agriculture and agroforestry, also suggests replacing the monoculture conifer windbreaks often planted around farms with edible windbreaks that include Persimmons.