Food forests are a form of perennial agroforestry modelled after natural forests. They increase food security, increase biodiversity, regenerate degraded land, store carbon, recycle nutrients and regulate microclimates. Indigenous peoples have cultivated food forests around the world for millennia, including in Ontario.

“Sometime around 1,200 years ago, this whole region was gradually converted to an Oak Savannah food forest, accented by prairie grasses and wetlands, by design. A food forest is essentially what it sounds like. It is a strategically designed habitat that focuses on building up several layers of the ecosystem to ensure food for all parts of that ecosystem throughout each of the seasons, with a long-term vision for generational thriving.”

— Mkomose (Dr. Andrew Judge)

Our food forest design principles

In 2017, during our design phase, we identified a set of food forest design principles:

- Edible learning lab: A space for intergenerational education and community engagement. Be a creative force for positive change in our community.

- Polyculture systems: Plants are not isolated entities, but participants in a system constantly in flux. Prioritize native, organic, heirloom, perennial and yield. Pattern the food forest after our biodiverse native forests.

- Reciprocity: By sharing our stories and shovels, our laughter and harvests, our gifts and our needs we build relationships and weave community. Encourage reciprocity so everyone experience the joy of giving.

- Beauty: Cultivate an appreciation for the wild beauty of the natural world, an interplay of woodlands, open landscapes and the transitional areas where they meet (edges or ecotones).

- Regenerative: Emulate natural ecosystems to increase soil health, capture rainwater and attract natural allies.

- Wellbeing: Promote mental, physical, and spiritual health

- Community: Encourage community connections, making the space inclusive.

Components of our food forest

Our permaculture food forest in the northwest corner is a diverse, multi-layer assembly of fruit trees (apple, pear, plum, persimmon, pawpaw, mulberry, peach), nut trees (pecan, butternut), berry bushes (saskatoons, currants, haskaps, gooseberries, blackberries, raspberries, goumi berries, sour cherry) and more interplanted with nitrogen fixing plants (goji berry, wild senna, wild liquorice, new jersey tea, leadplant, canada milk vetch), perennial vegetables (rhubarb, purple fennel, horseradish, asparagus, lovage), herbs (oregano, thyme, chives, garlic chives, anise hyssop), native plants and spontaneous plants (otherwise known as weeds). Permaculture food forest original plan.

Our welcome garden in the southwest corner is a polyculture meadow, with mulberries, apples, sour cherries, elderberries, aronia berries, hazelnuts and saskatoons. Welcome garden in original plan.

Our edible hedgerows — planted with elderberries, blackberries, raspberries, gooseberries, aronia berries, saskatoons, goumi berries, sour cherries and butternuts — shelter Lakeside from wind, provide privacy, serve as a wildlife corridor and provide food for humans and insects, birds, pollinators and other wildlife. Edible hedgerow in original plan.

Our edible little nut forest based is based on the Miyawaki Method of rapid native forest regeneration. We used the ecological land classification for Southern Ontario and FGCA’s species information tables to choose native and Carolinian species, including three varieties of oaks, shagbark hickories, black walnuts, red mulberries, American persimmons, elderberries, serviceberries, american hazelnuts, aronia berries, pasture roses and more. Little Nut Forest in original plan.

Food forests which inspired our design

Stefan Sobkowiak’s permaculture orchard

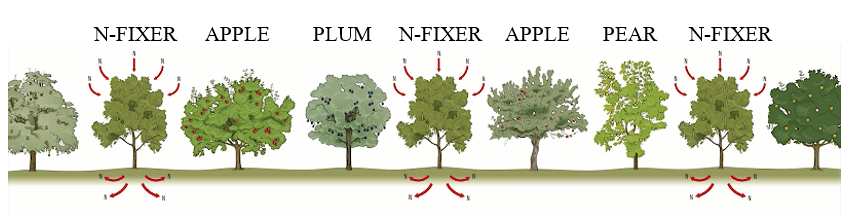

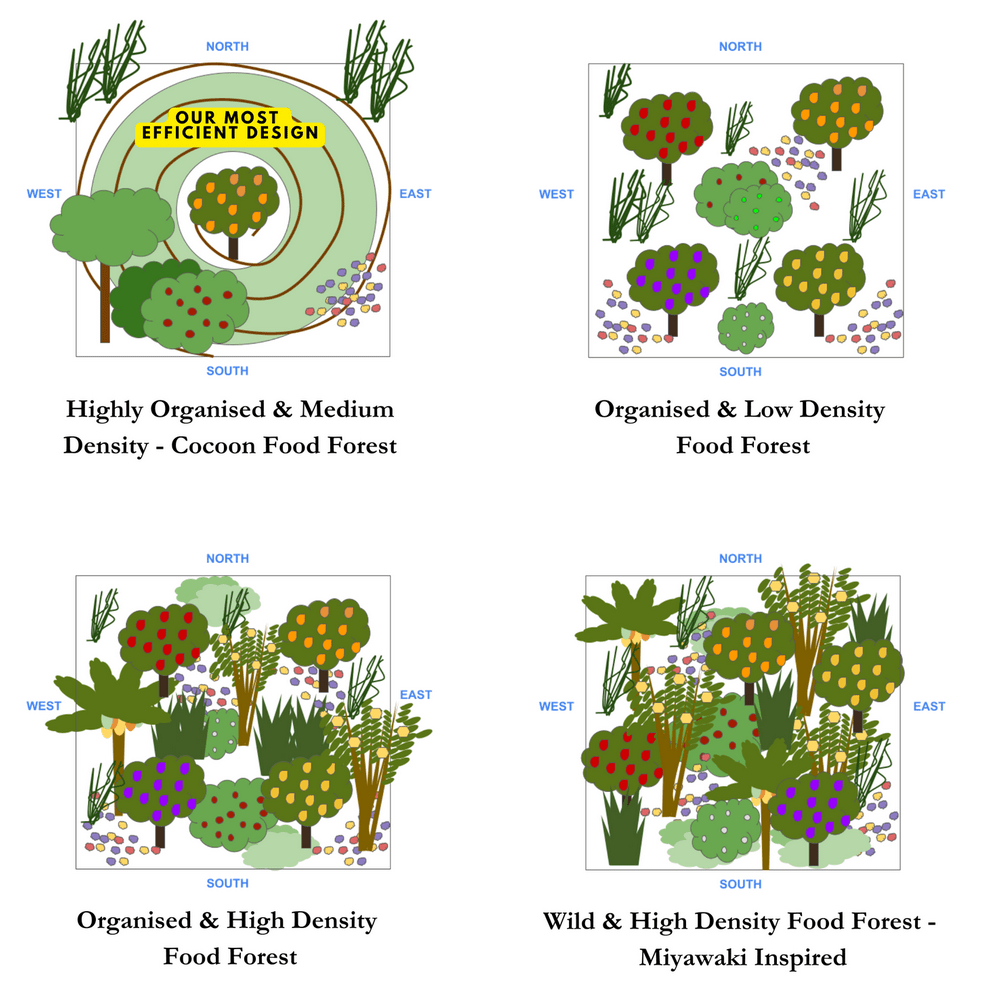

Stefan Sobkowiak’s permaculture orchard, looks to the forest edge and ecological design principles for inspiration. One of his most important design principles is the TRIOS model, planted as polycultures. Each TRIO includes a nitrogen fixer or support species, along with two different fruit or nut trees or cultivars. Ensuring no two trees of the same type are planted next to each other helps ensure good pollination and reduces likelihood of diseases or pests moving between the trees. The nitrogen fixers eliminate the need for fertilization.

Miyawaki method of rapid afforestation

The Miyawaki method, pioneered by Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki, looks to native forest ecosystems for inspiration. In a Miyawaki forest, over 30 different native tree and shrub species are planted at a density of three per square metre. Orchard of Flavours also experimented with the Miyawaki method for one of its food forest designs.

Due to the density, we know the productivity of the native nut trees, fruit trees and berry bushes in our little nut forest will be much lower than in our permaculture food forest. However, the little nut forest is extremely important for urban biodiversity, providing food and shelter for insects, pollinators, birds and more. Now that our little nut forest is established, it requires no maintenance. Over the next few years, to increase the diversity of wildlife supported by the little nut forest, we’ll be planting the forest edge with thicket forming wild plums, native blackberries, raspberries and wild roses.

We’re featured in this video of seven community food forests from around the world!

References

- The Food Forest Lab, Orchard of Flavours

- Community Orchards for Food Sovereignty, Human Health, and Climate Resilience, (Lovell et al., 2021)

- Philadelphia Orchard Project

- Insights from the Miyawaki method and syntrophic farming

- Woody perennial polycultures in the U.S. Midwest enhance biodiversity and ecosystem functions, Kreitzman et al., 2022

- Mimicking nature: a review of successional agroforestry systems as an analogue to natural regeneration of secondary forest stands, Katherine Young (2017)

- Tree architecture and functioning facing multispecies environments: We have gone only halfway in fruit-trees, Pierre-Éric Lauri, 2020

- A review of successional agroforestry systems as an analogue to natural regeneration of secondary forest stands, Katherine Young, 2017

- Modelling a nature analogous polyculture within a temperate forest garden system, Andrew Walton, 2024

- Community forest gardens: case studies throughout the United States, Katherine Favor